Falling

Le Pavé d’Orsay Galérie ∣ Paris

Solo Exhibition 2024

Jesus Mode

2024 Oil on Linen 162x114cm

-

Agatha

2024 Oil on Linen 81x65cm

-

All My Colours Bleed For You

2024 Oil on Linen 130x97cm

-

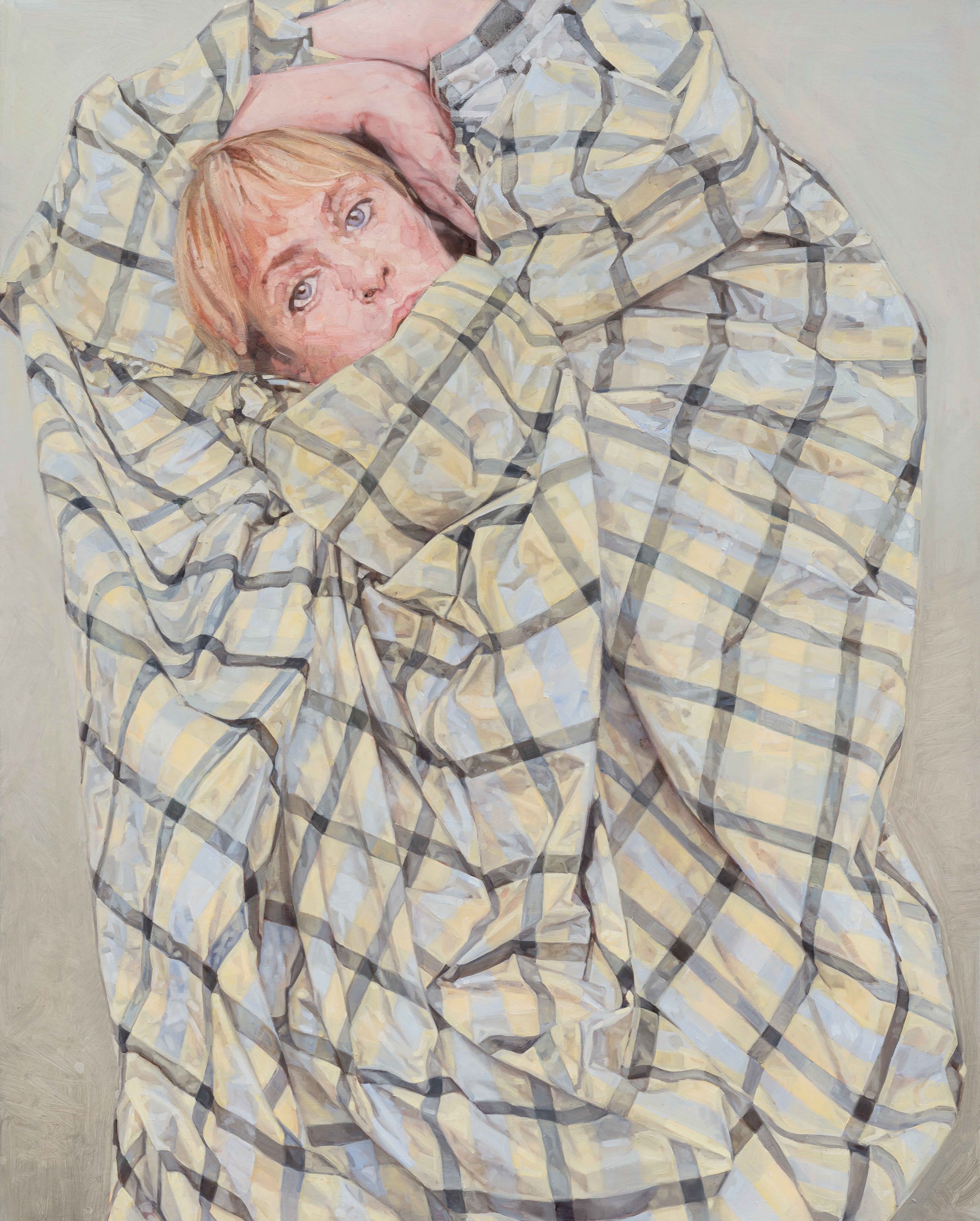

Hold Tight

2024 Oil on Linen 146x114cm

-

Lifting

2024 Dye on Silk 57x35cm

-

Lanterne

2024 Dye on Double Layer of Silk 47x50cm

-

Magenta Blue

2024 Dye on Double Layer of Silk 57x35cm

-

Providence I

2024 Oil on Board 35x27cm

-

Providence II

2024 Oil on Board 35x27cm

-

Providence III

2024 Oil on Board 35x27cm

-

Dream of Ascension

2024 Dye on Silk 57x38cm

-

This Could Quietly Fade Away

2024 Dye on Double Layer of Silk 57x38cm

-

Into You

2024 Dye on Silk 57x38cm

-

Pietà

2024 Oil on Linen 146x114cm

-

Jesus Mode

2024 Oil on Linen 162x114cm

-

With the Shadow

2024 Oil on Linen 81x65cm

-

Higher, Deeper

2024 Dye on Double Layer of Silk 57x30cm

-

Unfolding

2023 Oil on Polyester 130x97cm

Falling Essay

Lauren Caroll Harris

“The paintings are of giving and taking, needing and being needed, serving and being served, wanting love and reciprocation, reaching out and catching.”

The women and girls in ‘Falling’ could easily be read as types – the good mother, the over-attached daughter and so on. Or you could see them as psychologically complex individuals wrapped up in the profound existential experience nurturing children into adulthood. The paintings are of giving and taking, needing and being needed, serving and being served, wanting love and reciprocation, reaching out and catching.

Drawing on psychoanalytic thinking and Christian iconography, ‘Falling’ offers a series of portraits and staged tableaux reframing Mother as Christ, martyr and sacrificial entity. Mothers and daughters hold, lean on, carry and fall into each other, as if in crucifixion in the moments after being pulled from the cross-beam. They hold one another as Mary held Jesus after his descent from the cross, in the manner of the Pietà, another Christian image that recurs in Western art history. Their gravity-laden bodies are entwined in love and tension, in uncomfortable but necessary arrangements of human need. The mothers here feel all across the emotional spectrum. As feminist theorist Jacqueline Rose writes, “mothers cannot help but be in touch with the most difficult aspects of any fully lived life. Along with the passion and pleasure, it is the secret knowledge they share. Why on earth should it fall to them to paint things bright and innocent and safe?”

Clare is a figurative painter of the complexity of our matrilineal relationships. Her reworking of female martyrdom and sacrifice in the history of painting reaches further: one portrait has the attributes of Saint Agatha of Sicily, a holy woman who was tortured – her breasts excised – for spurning a Roman governor so as to retain her virginity. In apparition form, Saint Peter miraculously healed her wounds, and Agatha died in prison, praying till the end. Italian painters visually linked her suffering to Christ’s: ‘Agatha’ means good, and she is now venerated for her persecution. The perverse and the violent legacy of ecstatic, canonised Agatha lives on in many European museums.

In Jungian thought, you can be all archetypes at once: the villain and the saviour. Biblical thinking and iconography, imprinted on much of Western art history, is famously dichotomised: virgin, whore; carer, patriarch; innocent girl, fallen woman; angel, devil; good, evil. Both these schools fall within our unwitting inheritance, a theme of ‘Falling’.

In some of the works here, eras of life melt into one another across generations – childhood, pubescence, middle age. In all, the carer role is fraught and the body is vulnerable and interdependent. The blanket – usually a symbol of domestic security, and a nod to folded drapery in the Western painting tradition – recurs, but in these images, its folds conceal, cloak and veil, sometimes evoking a vulva. There is great fragility in these paintings, in which bruised oils are washed like watercolours and diaphanous silks carry entangled silhouettes in fluid magentas and blues. The hands evoke what Rachel Cusk calls “all that love and terror and strangeness” and Louise Bourgeois’ “Hands” (2002-2003), in which she rendered the psychological complexity of motherhood – her great, ambivalent subject – in red crayon traces.

The work of many successful women artists becomes tied exclusively to their biographies. When Tracy Emin makes an applique blanket work like Automatic Orgasm (Come Unto Me), 2001, we tend to read it as a diary entry. When Lucien Freud made expressive, private studies of friends and family in his domestic studio practice, we read it a gesture toward universality. Clare is in these fleshy paintings (explicitly, in one concealed self-portrait) but they are bigger than her and more than confessional. In ‘Falling’, I see a whole churning world troubling our assumptions about mothers in the lineage of feminine archetypes, and many other possible ones.